(<-- Mary Eliza (Chenevard) Comstock) (Back to Start) (Captain John Ellery (1681-1742) -->)

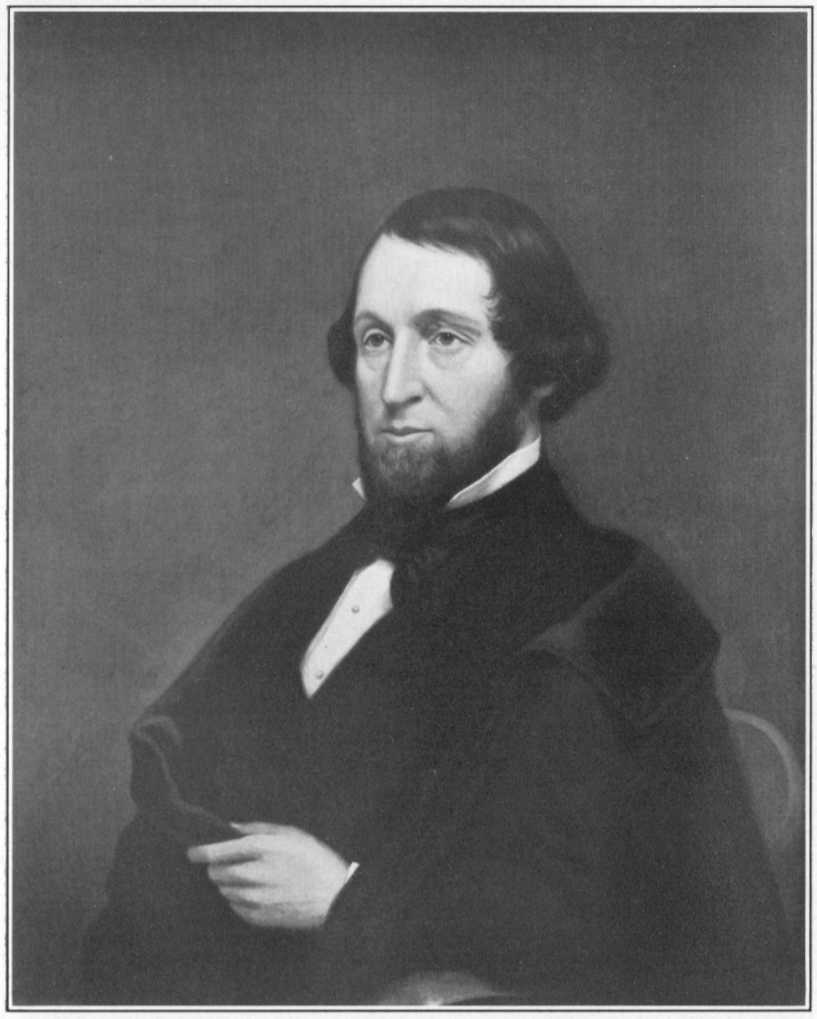

Governor Thomas Hart Seymour (1808-1868)

GOVERNOR THOMAS HART SEYMOUR (1808-1868)

Grandson of the First Mayor; graduated in 1829 from Partridge's Military Institute in Middletown; Commanding Officer of the Hartford Light Guard; admitted to the bar in Hartford about 1833; soon entered the public arena, for which his popular manners and address eminently qualified him; elected to Congress in 1843 from the Hartford District. In 1846 he was commissioned Major of the 9th New England Regiment of Volunteers in the Mexican War; in 1847, the Commanding Officer of his regiment having fallen in the assault on Chapultepec, Major Seymour led the troops, scaled the heights, and with his men was the first to enter the fortress, earning him the title of “Hero of Chapultepec.” Governor of Connecticut, 1850-53; Presidential Elector in 1853; U.S. Minister to Russia. During the Civil War, his sympathies were largely with the South; a leader of the Connecticut Peace Democrats, closing his career as a public man. The late Gov. Charles R. Ingersoll, who was a friend and great admirer of Gov. Seymour, and also a great gentleman, a great churchman and a great Democrat, told the author that at the height of his career, no man in Connecticut was more warmly admired than Tom Seymour.

From the portrait painted by George F. Wright (1828-1881), in Memorial Hall, Connecticut State Library.

“Capt. Thomas H. Seymour, from the same school, (Captain Alden Partridge's Military School) belonged to a family noted for its military training and spirit. He afterwards became the commander of the Ninth (New England) Regiment, in the war with Mexico, and was a gallant and chivalrous officer.” (Vol. 1, p. 186 Trumbull's Memorial History of Hartford County.)

First over the ramparts at the taking of Chapultepec, he was long referred to as the “Hero of Chapultepec.”

CHAPULTEPEC.

“The Hill of the Grasshopper,” is a bold projection of porphyry, rising two hundred feet above the valley. It was once an island in Lake Texcoco, is now fully four miles from the nearest shore. The Aztecs, who gave it the name which it now bears, occupied it in 1279, were driven from it by a neighboring tribe, but later regained it and built a temple on its summit. On the south side is a large spring, which is the water supply of part of the city. The castle occupies the site of Montezuma's palace, and is surrounded by a magnificent grove of old cypress trees, from which depend festoons of Spanish moss. A portion of the structure has been fitted up as a residence for the President, and the rest is occupied as the National Military School. The view from the ramparts and terraces is magnificent, comprising the city, with its many domes and towers, the surrounding fields and meadows, and the inclosing mountains, with Popocatepetl and Ixtaccihuatl standing proudly above all. We can describe the view from Chapultepec in no more fitting words than the following from the pen of Mr. F. Hopkinson Smith: “There are two views which always rise up in my memory when a grand panoramic vision bursts upon me suddenly. One is from a spot in Granada, called 'La Ultima Suspira de Mores.' It is where Boabdil stood and wept when he looked for the last time over the beautiful valley of the Vega–the loveliest garden in Spain–the red towers and terraces of the Alhambra bathed in the setting sun. The other is this great sweep of plain, the distant mountain range, with all its wealth of palm, orange and olive; the snow-capped twin peaks dominating the horizon; the silver line of the distant lake, and the fair city, the Tenochtitlan of the ancients, the Eldorado of Cortes, sparkling like a jewel in the midst of this vast stretch of green and gold.

“Both monarchs wept over their dominions. Boabdil, that the power of his race, which for six hundred years had ruled Spain, was broken, and that the light of the Crescent had paled forever in the effulgence of the rising Cross. Montezuma, that the fires of his temple had forever gone out, and that henceforth his people were slaves.

“Sitting alone on this parapet, watching the fading sunlight and the long creeping shadows, and comparing Mexico and Spain of today with what we know to be true of the Moors, and what we hope was true of the Aztecs, and being in a reflective frame of mind, it becomes a question with me whether the civilized world ought not to have mingled their tears with both potentates.” The delightful historian sums it up in this way: “Spain has the unenviable credit of having destroyed two great civilizations.”

GOVERNOR SEYMOUR'S RUSSIAN MISSION

It is more than likely that Governor Tom's personal papers and letters home to his family from Europe when United States Minister to Russia were destroyed at the time the old Seymour Homestead on Governor Street was dismantled and sold–that they shared the fate of that great accumulation of family and historic papers. Fortunately we get just a glimpse of him in the Mission in St. Petersburg through the eyes of Andrew Dickson White. When a young man just out of Yale, Governor Seymour invited White to be one of the attaches at the Mission in St. Petersburg. In his two-volume autobiography published in 1905, Mr. White recalls some of his experiences in St. Petersburg with Governor Seymour. We get a pleasing picture of the Minister and his young attache sitting in the Legation before the fire, after the official and social duties of the day. Mr. White says: “I find Governor Seymour a man of real conviction, thoroughly a gentleman, quiet, conscientious, kindly, studious, thoughtful, modest, abstemious, hardly ever touching a glass of wine, a man esteemed and beloved by all who really knew him.” (page 62) He further says of Governor Seymour that he “became one of the dearest friends I ever had.” Regarding the Minister's mode of life in St. Petersburg, Mr. White says, “The minister had embraced a chance very rare in Russia,–one which, in fact, almost never occurs,–and had secured a large house fully furnished, with the servants, who, from the big chasseur who stood at the back of the minister's sledge to the boy who blew the organ on which I practiced, were serfs, and all, without exception, docile, gentle, and kindly.”

Not long before Mr. White died, the author had a long talk with him in the Cosmos Club in Washington, during which Mr. White reminisced delightfully and with evident pleasure concerning life with Governor Tom at the Mission in St. Petersburg. Mr. White could not say enough in praise of Governor Tom's breeding and consideration of everyone attached to the Mission and, in particular, of all who asked his assistance. He was always willing to sacrifice his own time and convenience to others. Mr. White cites numerous instances of this. The author made notes of that talk, but cannot put his hand upon them at this writing. It is a tribute- to Governor Seymour's judgment and conception of the manner in which the Mission should he staffed, that he should have selected as attaches for the mission two men who were destined to have such notable careers of their own in after life as Andrew Dickson White and Daniel Cort Gilman. It is clear that Governor Seymour won the warm admiration of Czar Nicholas I and of his successor Alexander II. The Czar gave Minister Seymour a superb malachite table and other costly and interesting souvenirs, and as late as 1863, four years after the Governor's return from Russia, he refers to having received some volumes from the Emperor, and they were in themselves princely gifts. At the termination of his mission Governor Seymour spent about a year travelling in Europe and then, after an absence from home of nearly six years, he returned at the end of August, 1859, landing at the port of Boston, where he was met by members of his family and two friends who were to assist in the public reception planned for his return to Hartford. The party soon left Boston for Springfield and from Springfield they went on to Hartford where the Governor arrived in time to enter a barouche drawn by four black horses which took its place in the parade which attracted people from far around. The city was gay with bunting and banners as it had not been in its entire history. It may be doubted if any citizen, public or private, was ever given such a reception in Hartford before or since. The line of parade was something over a mile long, including people on horseback, in carriages, and on foot. Altogether there were something more than fifteen bands in the parade, which included the Seymour Light Infantry, the Governor's Horse Guards, and the Putnam Phalanx which had been organized while the Governor was in Europe chiefly for the purpose of participating in his reception home. An address of welcome was made by the Honorable Isaac W. Stuart to which Governor Seymour made an appropriate reply. The Hartford Times, the Hartford Courant, and Hartford Post of the time contain glowing accounts of the reception, testifying to the affection and admiration with which Governor Seymour was regarded. After reading these accounts of the affair, one can better understand the statements that Governor Seymour was at this time in his career the most beloved man in the State of Connecticut.

THE SEYMOUR DEMONSTRATION

ENTHUSIASTIC RECEPTION OF COL. THOMAS H. SEYMOUR

The man who has so riveted himself to the affections of the people as to he received in the manner in which Col. Thomas H. Seymour was received in this city yesterday, may well be proud of his position. Col. Seymour, after an absence of six years, four of which were spent as a representative of the United States Government at the Court of St. Petersburg, a position which he filled with credit to himself and honor to his government, now returns to his native country and the city of his birth as a citizen, and yet he is received with all the pomp and display, and a great deal more real enthusiasm than would be extended to the most exalted dignitary in the land if he should visit us. This demonstration in honor of Col. Seymour must be all the more gratifying to him from the fact that it is not bestowed on account of any official position which he now holds–it is the man that is honored–not alone by his political friends, hut by men of all parties, old and young.–Prom the Hartford Post of August 31, 1859.

(<-- Mary Eliza (Chenevard) Comstock) (Back to Start) (Captain John Ellery (1681-1742) -->)